Heel Striking vs Forefoot

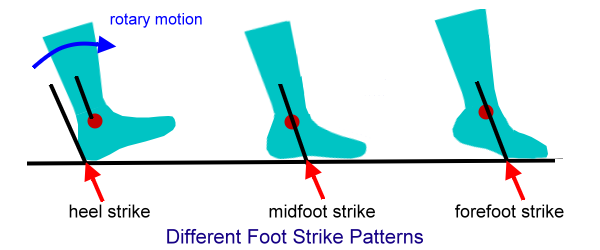

One of the most hotly debated topics in any sport of running is heel striking vs. forefoot and mid-foot striking for running. The minimalist and barefoot phase was ushered in around the same time that more “functional” training came back into the fitness scene. Fancy equipment and machines fell way to older movements and routines that mimicked movement patterns better for real-life application. Many people have switched over to landing on the balls of their feet or the middle of their foot. But if you look at the masses, people are still heel striking when they run. Let’s take a second to examine how this became so popular.

Do you remember running around barefoot indoors or in the backyard as a kid? Were you running on your “toes” or were you landing on the ground with your heels first, and rolling forward and bounding off your toes? I can remember running barefoot when I was younger and instinctively I ran on my toes. I knew I was quicker and far more stealthy running on my toes than how I ran when I wore shoes. But when I was wearing shoes, I was definitely heel striking. It’s funny that most of us never realized there was a disconnect in how we ran differently barefoot than with shoes. When I ran track in high school and college we would practice in our running shoes and heel strike. But as soon as we put spikes on to race or jump, we switched to running on the balls of our feet. Our coaches never told us to run that way, or to keep the styles the same despite the shoe or event. Why did we do that? In hindsight, it didn’t make sense at all to train heel striking and then race on the balls of our feet.

But it isn’t a massive surprise that almost all of us made this switch. Once we are able to walk on our own, our parents put us in tiny little shoes because they’re so freaking cute and they don’t want us damaging our feet walking everywhere. Well if you’ve ever tried running on the balls of your feet with conventional running shoes, it’s a lot more difficult and less effective than barefoot or with minimalist shoes on. The reason for this is conventional shoes have a raised heel. This will put your foot at an angle that is highest at the back and lowest at the front. So if you’re landing on the balls of your feet, your foot needs space to bound and return energy. But with shoes that have big heels, all that space is reduced. This makes it much more convenient to simply land on your heels first, and roll the foot forward to the toes, and bound from there just like you would with running on the balls of your feet. If you’ve ever landed on your heels first when running barefoot, you know it hurts. So it’s natural to land on your toes or the middle of the foot. But when that raised heel is in the way, it’s much more likely to hit the ground first, and all that padding makes it rather comfy to do so.

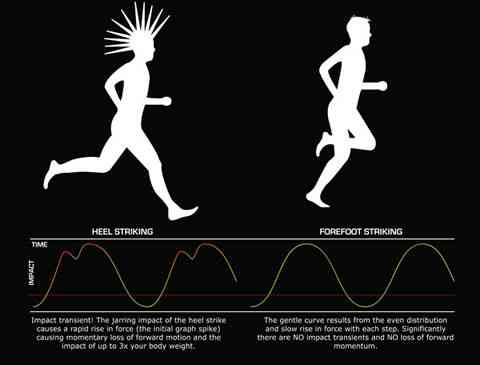

Why are we landing on our heels? Our heels are bone, and are not built with any muscles to provide a stretch reflex to return energy. When we land on our heels while running, we are simply stomping into the ground with a lot of energy that ends up being absorbed into the ground and sent right back up our legs and spine in a shockwave, because the surface we are running on is hard and doesn’t absorb or return energy well. Here’s a good illustration of this fact: stand with your knees locked and jump off your heels only without bending your knees. Having a tough time? I imagine you are, because it’s not possible! Now even bend your knees and try jumping off of your heels. Getting far? Now stand the same way with your knees locked out and try jumping off the balls your feet without bending your knees. Ah see, now we are getting somewhere because you are able to flex and extend the muscles in your arches and your calves to produce power and return energy. Heel striking entails losing energy from landing at the heel, sending shock up the body, only to bound off the front of the foot at the end. Why not just land and bound off the front of the foot and use the momentum landing to bound off the same spot without losing anywhere near as much energy?

Heel striking entails extending the leg far in front of the center of gravity of the body and then using the hamstring and momentum to pull the body forward in order to change steps and continue the running cycle. Every single step we do this, we cause nasty shearing forces on the knee. We are trying to move our bodies in a forward motion quickly, but with every bound we step in front of us and slow ourselves for a fraction of a second, until our body’s momentum and muscles overpower that energy and keep propelling us forward. Kelly Starrett likes to use the analogy that we are driving a car with the emergency brake on. It’s been well established that most heel strikers (since most are novice) tend to over stride. When we look at heel strikers deemed more advanced or elite, we see a much shorter stride out in front of the body. Heel striking can also yield up to 6x more vertical oscillation. So if you weigh 180 pounds, that’s 1,080 pounds with each step your body is absorbing in a bad position. At 300-330 steps per ¼ mile, you’re looking at over 1.4 million pounds absorbed (and much less returned) every mile.

Heel Striking vs. Forefoot Efficiency

Here is where many of the debates take place as to which style is best for running: efficiency. When we look at track athletes competing in shorter domains of distance and time, a very large majority of them (around 90%) are running forefoot and mid-foot. Once we start approaching anything past 10k, we see quite the opposite as far more runners transition to a heel strike. This is the case from beginners all the way to the elite runners and record holders. Unfortunately there have not been a lot of studies carried out to shed light on the efficiency of all styles. The Lieberman study convinced a lot of people to switch from heel striking, when he showed 88% of Kenyan barefoot runners landed at the mid or forefoot when running at their own pace on a dirt road [3]. But the Hatala study from 2013 opened Pandora’s box again when his study showed a different barefoot Kenyan tribe heel strike significantly more at about 70% [2]. The heel striking community rejoiced! But, they didn’t read the study…they simply read the abstract or a summary. We need to actually read studies, since often times the interpretation of results and what actually happened differs largely.

Right away the Hatala study acknowledges that the tribe in this study ran less habitually than the tribe in Lieberman’s study, which averaged about 20km a day under observation. That changes the entire outcome right off the bat. In the Hatala study, the participants were simply running on a 15m track of packed sand, which was described as “firm” but it’s nowhere near as hard as a dirt road; this alone makes a huge difference in the comfort of heel striking barefoot. The participants were told to run at a comfortable endurance pace, and then three more times at a faster pace. A pressure pad was placed halfway down the track. At an 8 min./mile pace, 72% of the runners landed on their heels. At the fastest pace of about 3:50-4:30 min./mile (so pretty freaking fast) the percentage of runners landing on their heels plummeted down to 40%, meaning 60% of them landed at the mid or forefoot. So even though Hatala’s participants only ran 15m at a time, they still switched to mid-foot and forefoot striking the faster they went. If they had been running anywhere near the distances that Lieberman’s participants were (and on a similar hard surface), we would most likely see a much higher rate of mid-foot and forefoot striking again. Hasegawa in 2007 showed very similar results; runners changing their stride from heel striking to mid-foot and forefoot the faster they had to run [1].

A Spanish study in 2014 also highlighted runners being more economical with heel striking, but once you read the science, it showed the opposite again. The slower the running pace, the more economical heel strikers were. The faster the pace, the less economical they became. At the fastest speed there was no “statistically significant” difference, which is odd (or is it?). When we look at the numbers of cadence (steps per minute) and step length of all the runners, it’s virtually identical. This is great to see because mid-foot and forefoot almost always translates to a shorter stride length, and thus a higher step cadence. But in this study, the heel strikers had the same stride length and cadence, suggesting they were landing far closer to their center of gravity near the hips than most heel strikers who step far out in front of their bodies.

Many advocates of heel striking will agree that not all heel strikes are created equal. When heel strikers land with the foot too far in front of the body, it causes the excessive braking that we mentioned earlier (gas-o-brake-o), resulting in temporary loss of forward movement. It also entails the foot will greatly flex the tibia muscles just to enable the heel to land first instead of the mid-foot or forefoot (the larger the heel of the shoe, the more you need to lift your toes/flex your tibia). The flatter the foot is upon landing, the better heel strike it is due to less load on the joints of the legs. So we are starting to see some similarities in what heel striking advocates deem “good heel striking” and mid-foot and forefoot striking: foot landing much closer to the hips and the body’s center of gravity, also causing a shorter stride and higher cadence. This is one of the biggest arguments to employ mid-foot and forefoot striking.

Heel Striking vs. Forefoot Injury

Running causes more injuries in exercise than any other form of exercise by far. This is also easily biased since most people who exercise run. It is free, thought of as a good way to stay in shape and it is easy to do. Heel striking is notorious for its knee injuries, shin splints, hip problems, and “plantar fasciitis”. Burning a hole in your kneecap and torturing your meniscus plagues many people, I deal with them all the time. But when the barefoot and minimalist craze came about, it got bashed when the incidence of injury increased, specifically the ankle/foot and calf area. Instead of placing large loads of energy/shock on the knee, hip, and spine from heel striking, more tension is placed at the ankle and arch of the foot. This is an unfair assessment and judgment of mid-foot and forefoot striking. When you take someone who has worn heavily padded shoes with raised heels their entire lives, and then all of a sudden give them a minimally padded shoe with little to no heel, it is a drastic change. Your heel cords have been drastically shortened due to decades of not being used to full range for walking, standing, jumping, and running. When people switched over to the new footwear, how many do you think thought to strengthen their feet to create a stronger and stable arch and Achilles tendon? None. Some may have eased into it by walking and jogging slowly. But most of us are impatient and we just want to GO! Now all of a sudden people have no giant heel to absorb the shock, and way less padding to support their arches. Many switched over to landing mid or forefoot, and are using their arches to rebound far more of the energy, causing the Achilles tendon to stretch waaaaay further than it’s ever been used to and return energy. Of course this is going to cause a lot of injuries. Heel striking also will cause far more oscillation vertically for a runner, increasing the stress the body absorbs.

Heel Striking vs. Forefoot : So Which Is Better?

This causes huge debates whenever it is brought up. Heel strikers are going to say that their form is more efficient, and that the elite distance runners are mostly heel strikers. They’re going to say the incidence of injury is too high for mid and forefoot striking. Mid and forefoot runners are going to say all the sprinters run mid and forefoot because when speed counts, heel striking doesn’t let you. They’re going to list off the knee injury rates. Heel strikers are going to say there’s good and bad heel striking, and mid and forefoot strikers should say the same thing. There’s certainly still plenty of poor biomechanics that can be displayed with a mid and forefoot strike. There can be excessive force placed at the knees, hips, and spine with any running style depending on how good a runner can maintain form and the function of his/her tissues. Where they can agree at some middle ground is that when the foot lands closer to the hip and thus closer to being behind the center of gravity, the better off the runner is. The flatter the foot lands to avoid the heel slamming into the ground too hard, the better off the runner is. The bigger a heel in a running shoe, the more compromised an athlete’s mechanics will be, especially with heel striking.

With heel striking we still see many runners utilizing the smaller muscles of the hip flexor to pull the legs forward instead of the large hamstring muscles. This compromises the hip function of athletes in comparison to those running on the mid-foot and forefoot. You can be injured with any style of running, depending on the function and mobility of your tissues and how you have been training in the past. We usually take 300-350 steps to run 400m. That’s thousands upon thousands of repetitions to run a few miles. When people are running several to dozens of miles a week in the same fashion, they have built some serious muscle memory and deeply engrained movement patterns. This means certain tissues being strong and supple, and other tissues being weak and aggravated. Switching to a new style utilizing other tissues more than others can take a long time and careful progression.

I don’t care what might win a race faster; I care what makes a better athlete and what is mechanically correct. A mid-foot and forefoot strike is more mechanically sound, and thus carries less long-term effects. The only way to measure the long term effects are to start following kids who never wear raised heel shoes in their life, and continue to run mid and forefoot as they naturally do without shoes.

If we don’t have a stable arch, it translates trouble for every way we move on our feet. The Achilles heel is pulled off axis, the ankle can be impinged, the knee is compromised, the hip internally rotates when it should externally rotate, and it travels up the kinetic chain of the body. It makes more sense to constantly land under the hip and allow gravity to keep us moving forward rather than stepping and landing out in front of our bodies every time. If we can’t jump and bound off our heels, we shouldn’t do it when we run. Proper training and progressions can make transitioning from heel striking to mid-foot and forefoot running fairly safe and easy. If we run mid-foot and forefoot barefoot as children, we shouldn’t be heel striking as adults.

1. Hasegawa http://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/abstract/2007/08000/foot_strike_patterns_of_runners_at_the_15_km_point.40.aspx

2. Hatala http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0052548#pone.0052548-Nigg1

3. Lieberman http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v463/n7280/full/nature08723.html

4. Spanish Study http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24002340